A Black southerner who grew up during the dying years of Jim Crow journeyed north as a young man to pursue life as a writer and scholar. Fate brought him back, and he fell in love with a troubled part of the state known around the world as the birthplace of the blues.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the Outside app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

The flat fields of the Mississippi Delta seem endless, and they can magically transport a traveler into the past. Sometimes when I’m driving through a stretch of this crescent-shaped part of northwest Mississippi—not to be confused with the region hundreds of miles south of here where the Mississippi River flows into the Gulf of Mexico—I look at the landscape and feel like I’m in one of those classic shots taken by a Depression-era photographer like Dorothea Lange. I know those photos intimately from the pages of books, but when I’m here, I’m also wandering through the early pages of my life.

My family once lived in the Delta, and I’ve been visiting it since I was a child. But if I’m being honest, I didn’t fully appreciate the richness of this place until I was well into middle age, when I came back to Mississippi to teach after decades of living in the Northeast.

I’ve always been fascinated by the dramatic drop you experience just north of Yazoo City—near the southern end of the Delta—when your car goes down a hill and, suddenly, the land looks tabletop flat for as far as you can see. In my mid-forties, to connect with the memory of my younger self, I began driving Delta roads as a pastime. Later I began to wander from them and ramble through towns with a litany of colorful names—Midnight, Alligator, Panther Burn, Egypt—unsure what I was searching for. Now, at age 65, I’m still driving around, with a new and profound sense of wonder.

Although this is a southern space, it’s also an ancient one. Formally known as the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta—named for the rivers that made and shaped it—the region was formed long before national political and racial divisions were projected onto our borders and into our consciousness. If you go back 15,000 years, when glaciers were melting and what’s now the Mississippi River flooded often, the lower Mississippi valleys were buried under a thick coating of alluvium. Dark, fertile soil was deposited here, creating some of the richest agricultural land in the world.

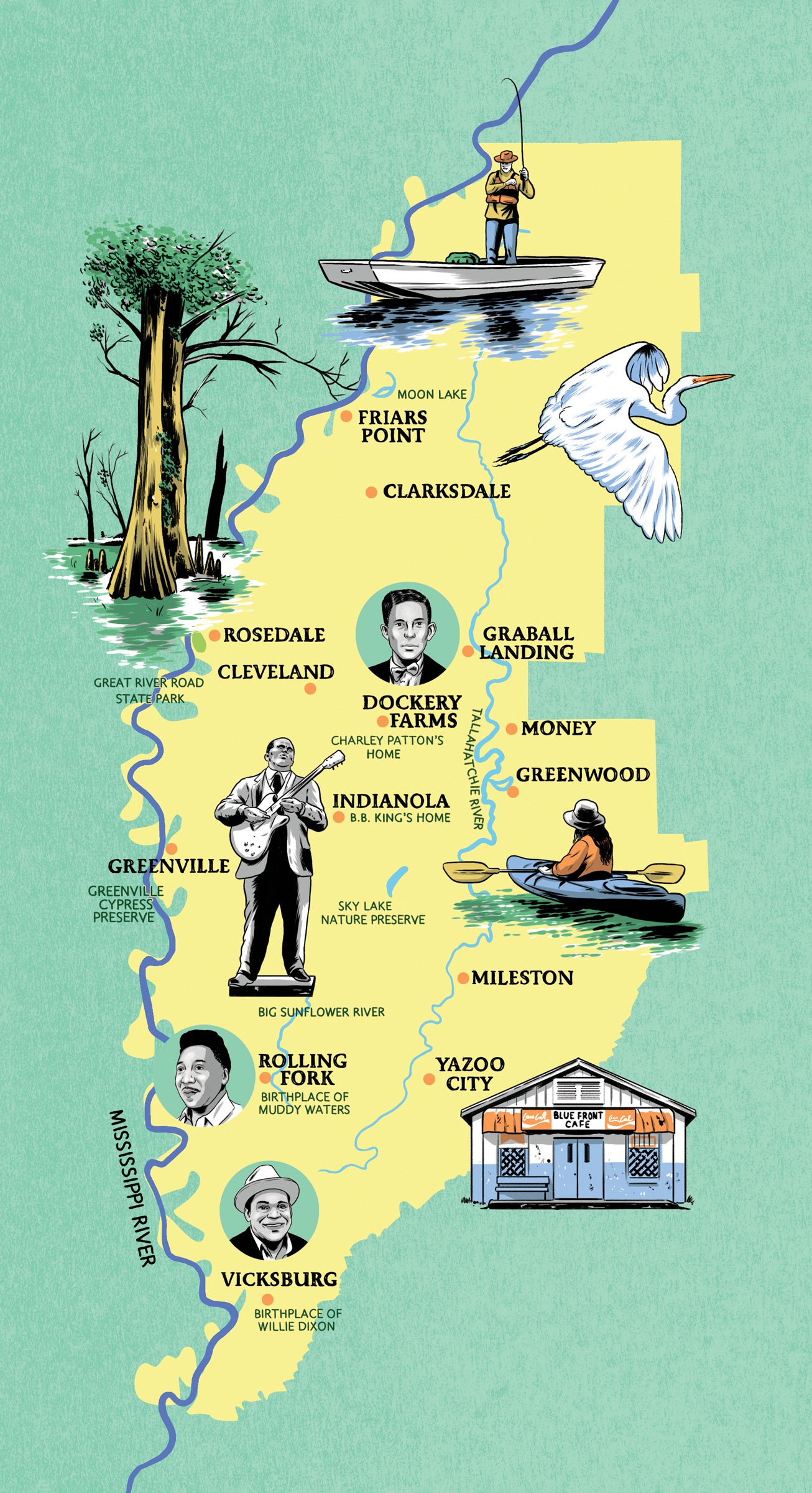

The eastern side of the Delta is defined by a line of bluffs, some rising 200 feet, and the western boundary is the Mississippi River itself. The result is a huge plain that extends roughly from Memphis, Tennessee, to Vicksburg, Mississippi. The Delta is the most photographed part of the state, making some people think that it’s bigger than it really is. But it’s quite large: 7,110 square miles, about one-seventh of Mississippi’s total area.

The fields of the modern-day Delta serve as a direct contrast to the primordial environment. When I drive up from the south, I head north out of Yazoo City through my family’s old stomping ground in the towns of Mileston and Tchula, then along the eastern edge of the Delta, with the bluffs visible in the distance. As I drive, I think about how these agricultural expanses are essentially a created environment: The land was partially cleared of jungle-thick stands of trees, mostly hardwood and pine, not long before the Civil War, through the toil of enslaved people. Later, more land was cleared by the descendants of slaves, who farmed under a system of sharecropping that mirrored the inequities of bondage.

I have a poor sense of direction, but I never get lost on my meanderings; memory functions as an inner compass. And because I choose to roam, randomly searching for the next enchanting spot—on land or near rivers like the Mississippi, the Yazoo, the Tallahatchie, the Sunflower, and the Big Black—I have come to engage with the land in ways that weren’t possible when I was riding shotgun next to my father as a boy.

This land was partially cleared of jungle-thick stands of trees, mostly hardwood and pine, not long before the Civil War, through the toil of enslaved people.

Much like the river on its western edge, the Delta’s story is one in which beauty and pain are indelibly linked across time. This is a land defined by the blues music that once seemed to wail across tall flood-protection levees and every furrow plowed into the dirt. (Among the blues greats with roots in the Delta: Willie Dixon, Muddy Waters, B.B. King, and Charley Patton.) Developed during an era of censorship, suppression, and persecution, the blues is a musical form that conveys the individual sorrow and collective tragedy that have been foisted on the Black people of the Delta. But the blues was also a source of pride, providing a creative outlet to resist the oppression of the plantation system. And that pride is wrapped up in the beauty of this place, a beauty that exists alongside the scars of the past.

Engaging with the Delta landscape helps me explore its stories with greater clarity, and many of these stories—like the 1955 murder of 14-year-old Emmett Till—are horrifying. Sometimes when I’m driving up the eastern edge of the Delta, I stop at Graball Landing, the spot along the Tallahatchie River where Till’s mutilated body was found after he was killed by two white men for allegedly “wolf whistling” at a white woman at a grocery store in a tiny town called Money. His lynching—and magazine photographs of a face disfigured by brutal beatings—helped launch the modern civil rights movement.

After visiting the landing, I take a walk along the Tallahatchie shoreline. I remember that Till’s mother said she hoped he did not die in vain. I remind myself that he eagerly anticipated his trip from his home in Chicago to visit relatives in the South. And suddenly, I realize that the freedom I feel walking next to this river is what he wanted to experience when he came here. My visit and my walk connect me with his legacy. But Graball Landing also connects me with my family’s past.

My father, Warren Eubanks, arrived in the Delta in 1949. He was a young, idealistic World War II veteran, an Alabama native, and a recent graduate of Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute, a pioneering Black college in Tuskegee, Alabama. With an agronomy degree in hand, he moved to Mileston, an all-Black New Deal resettlement community aligned with Tuskegee’s particular ideas about racial uplift. Established in 1940 on land that had once been a plantation, the federal project at Mileston was designed to transform the lives of 110 families—former sharecroppers who would become landowners. My father’s title was “Negro county agent,” which meant that he advised Black farmers in Mileston’s surrounding county, Holmes.

My parents had met at Tuskegee and married in 1951, and my mother, Lucille Richardson, then moved from south Alabama to the Delta, where she taught elementary school in Mileston. She was skeptical about Washington’s view of agriculture as a means of Black progress. Like the unnamed Black narrator in Ralph Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man, she wondered whether heavy reliance on practical vocations was misguided, stalling progress through lowered expectations about what Black people could achieve.

Both of my parents were products of the segregated South, but my mother had been raised in an interracial family whose very existence defied Jim Crow. Lucille, who looked white, knew the rules of segregation, but her family never really followed them. That had to change when she arrived in the Delta.

In the years immediately after the Supreme Court’s 1954 decision striking down “separate but equal” schools in Brown v. Board of Education, there was a harsh backlash of white resistance in the South—not only to school integration, but to Black progress in general—and the Delta became dangerous, especially for a couple who refused to follow the racial script society had handed them. Emmett Till’s murder served as one sign of looming hostility. There were many others in mid-1950s Mississippi, since it was effectively open season on Black people during that period. As educated professionals, my parents had a target on their backs.

My father understood that staying in the Delta, and doing public work to help advance his race, could cost him his life. My parents moved to south Mississippi in 1956, a year before I was born. I learned from later trips with my father to the Delta that he never wanted to leave. And that’s part of why I keep coming back: I need to understand the society he inhabited, and to work through feelings I have of survivor’s guilt.

One of my childhood friends, Edward Vaughn, once said to me—not in anger, but as fact—that if my family had stayed, the way I view the world would be completely different. He grew up in the Delta town of Clarksdale, the son of a Tuskegee graduate who’d chosen to remain after my family left. I grew up on a safe, isolated 80-acre farm near a town called Mount Olive, a place Edward visited regularly, experiencing a sense of freedom he didn’t have in the Delta. His point was that my relatively comfortable upbringing gave me a more expansive view about what I might be able to achieve in places far away from Mississippi.

Both my father’s longing and my friend’s comment led me to spend years studying the history and culture of the Delta. During my time back in Mississippi—and particularly through interviews and conversations with local residents—I’ve witnessed firsthand how economic shame creates a sense of powerlessness and isolation among the people here. (There’s a great deal of agricultural wealth in the Delta, but the 13 counties it comprises, which are all more than 50 percent Black, consistently suffer from some of the highest poverty rates in the nation.) I’m now writing a book about the Delta, with the aim of revealing why the sources of struggle are so persistent. I also hope to offer what might be a path forward, away from the shadows of the past.

No, I didn’t grow up here, but my history is here. To tell the complicated and layered story of the Delta, I seek out spaces that appeal to my lifelong love of the outdoors. It’s during my walks, hikes, and bike rides that I’ve come to have an even more profound connection to this land.

In springtime, the Delta’s freshly plowed fields reveal rich, loamy soil that will be hidden once summertime crops like cotton and soybeans are growing. Heavy rains often fill the deep ruts that run between symmetrical rows, making them look like miniature canals. The sight serves as a reminder that, over a period of centuries, rain and floods shaped this terrain into what it is today, and will keep shaping it until the end of time.

The Delta is like my own Sargasso Sea, a liminal space of mystery and madness where my thoughts move between the darkness of the past and the light that can be found in nature. I’ve come to realize that, to understand the Delta, you have to experience it not just through the history and rhythm of the blues, but through the struggles and stories that created the music. The blues isn’t just about pain; inside the songs are hidden cries for freedom and liberation. And the only way to connect with the spirit of those ideas is to connect with the land.

That’s why I love stopping and walking beside the fields. Sometimes I’ll bring my bike and ride empty roads to get closer to the scenery and experience the silence. When I begin to look at all the facets of the Delta—the topography, the culture, and all its natural and man-made beauty—I see a story not just about this place, but about America itself.

The Delta is like my own Sargasso Sea, a liminal space of mystery and madness where my thoughts move between the darkness of the past and the light that can be found in nature.

There’s nothing more American than the Mississippi. It’s one of the world’s major river systems, and a timeless literary inspiration. As Mark Twain wrote in Life on the Mississippi: “It is a remarkable river in this: that instead of widening toward its mouth, it grows narrower; grows narrower and deeper.” In the Delta, that means the mighty and muddy Mississippi can be explored by canoe, because it’s possible to find water that’s deep and calm. After paddling a while, you can have lunch on magnificent sandbars placed there by time and hydraulics. That section of the river shows few signs of civilization, except for the occasional passing tugboat.

Today, unfortunately, there are fewer places where you can simply stand and watch the river flow. As a boy, I loved going to Great River Road State Park, the only place in the state where you could camp on the banks of the Mississippi and commune with its motion. But a major flood in 2011 led to Great River Road’s closure as a 24-hour park; it’s open only for day use now. My dream is that, in the future, it will be restored to its former glory.

One of the great things about exploring the Delta in spring is that much of its natural beauty can be taken in on foot. On the edge of the Sky Lake nature reserve, north of the town of Belzoni, you can still experience the land’s unique qualities. With trees that date back to before the clearing of the Delta—including a massive 2,000-year-old cypress—you get a sense of what the scenery was like before it was subsumed by the engine of industrial agriculture.

Yes, this is an overwhelmingly flat land, but during spring one need not worry about the relentless heat, often unrelieved by shade, that’s part of everyday life here come summer. Once you explore the natural beauty of the Delta, it becomes difficult to shake from your consciousness. I’m often reminded of Wim Wenders’s 1988 film, Wings of Desire. In it a lonely angel wanders the streets of Berlin and encounters a dying man lying on a sidewalk. As the angel sits to comfort him, he urges the man to think of the memories he will take with him from this corporeal realm into the next life. As the man reflects on his time on earth, he suddenly recalls that one of his most beautiful and lasting memories was seeing the Mississippi Delta.

In Friars Point, the evening sun descends with an air of southern charm that masks the sorrow underlying the land’s blood memory. While sunsets in the American West are more dramatic, with their skies streaked lipstick red above mountains and mesas, the dimming of the day feels haunted here. As I walk along the top of a levee, I sometimes imagine the song many of the workers sang to the setting sun, which they called “Ol’ Hannah.”

Go down, ol’ Hannah, doncha rise no more

If you rise in the morning, bring Judgment Day

Go down, ol’ Hannah, doncha rise no more

If you rise in the morning, set the world on fire, set the world on fire

During these walks, I often think of the disconnect between the peace I feel and the pain of those who built what lies beneath my feet. An intimate connection with the Delta’s landscape doesn’t erase its past or its problems, nor does it hide them away. Encountering a place that many claim to know but few choose to understand leads not only to lasting memories, but also to a deeper understanding of this country. To change what we see on the Delta’s landscape, we must change what we know about it. And the only way to do that is to walk its fields, levees, wetlands, and sacred spaces to connect with the land itself.

A great way to explore the Delta is to look for the roadside markers on the Mississippi Blues Trail, which highlights more than 200 sites around the state with a significant connection to the history of blues music. The Delta’s 13 counties have the highest concentration of these gold-lettered blue placards. For more information, including a map and an app, check out msbluestrail.org.